The Milton Sanderson Amber Collection at PRI represents the first collection of early Miocene Dominican amber ever made, and the only unbiased collection in existence.

All other Dominican amber collections in the world are biased because they typically come from commercial sources and so, are “cherry-picked.” The Sanderson collection is still raw and unprocessed—it hasn’t been screened for inclusions yet. PRI researchers and volunteers will be able to screen the amber and keep all the inclusions they find; nothing will be discarded, keeping the collection unbiased.

History of the collection

Milton Sanderson (1910–2012) was an entomologist specializing in the taxonomy of beetles, who worked at the Illinois Natural History Survey from 1942 until his retirement in 1975. During his long career, Sanderson traveled widely pursuing his interest in Phyllophaga beetles.

In 1959, Sanderson traveled to the Province of Santiago in the Dominican Republic to do fieldwork. There he gathered the collection’s 160 pounds of amber—roughly 140,000 individual pieces—and shipped it back to the United States.

A year later, Sanderson and his colleague Thomas Farr described the formation Sanderson had collected from in a paper, published in Science.

Sanderson retired in 1975 and the amber was placed in storage and was subsequently “lost.”

Paleontology curator Sam Heads located the lost buckets of amber underneath a sink in the University of Illinois Natural Resources Building in 2011.

Conservation of the collection

The Milton Sanderson Dominican Amber Collection is in need of urgent conservation due to the approximately 40 years it was “lost” in storage.

The amber was thankfully not in contact with UV light, but it was subjected to temperature and humidity fluctuations while it was stored under a sink. At the time it was placed in storage, it was not known how heat and humidity affect fossil resins. More recent research shows that UV radiation, temperature, and humidity all play a role in the stability of fossil resins, which degrade when exposed to these adverse conditions. Amber should be kept in the dark, and not exposed to significant fluctuations in temperature or humidity.

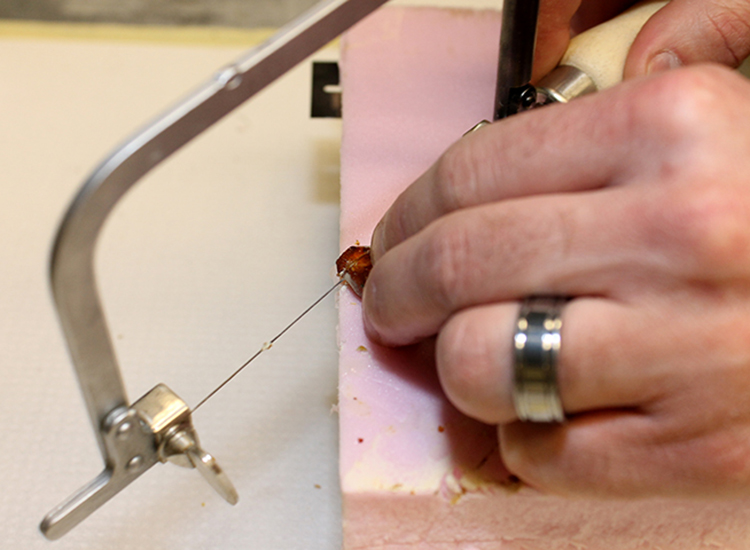

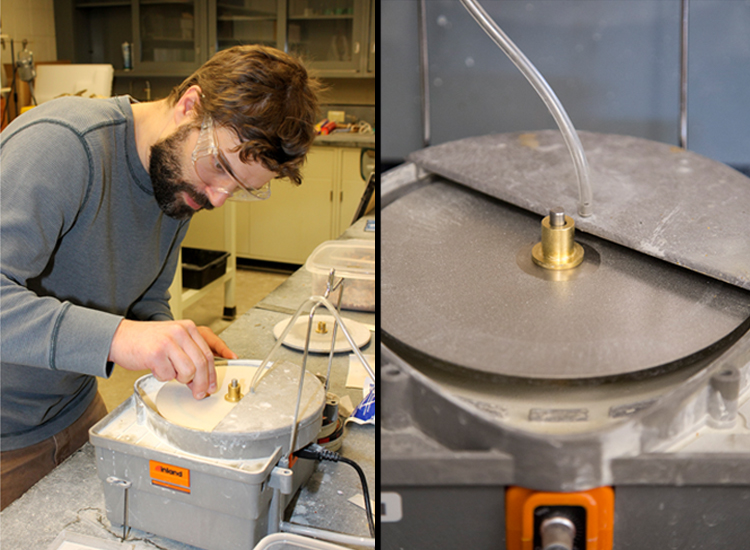

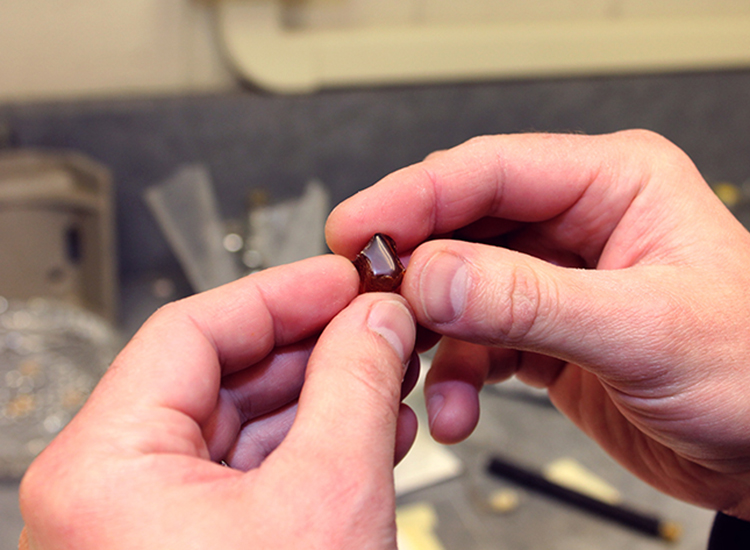

The gallery below shows the step-by-step process required to curate a Sanderson Collection specimen. Steps not shown are the vacuum-embedding of the fossil resin in epoxy resin to protect it from adverse conditions (for example, heat, humidity, UV, and drops/breaks). An added benefit of epoxy resin embedding is that it provides optical clarity by filling the crazing, or micro-fractures, in the amber. Each specimen in the Sanderson Collection will need this level of conservation to ensure its survival for future research.

Specimens from the collection

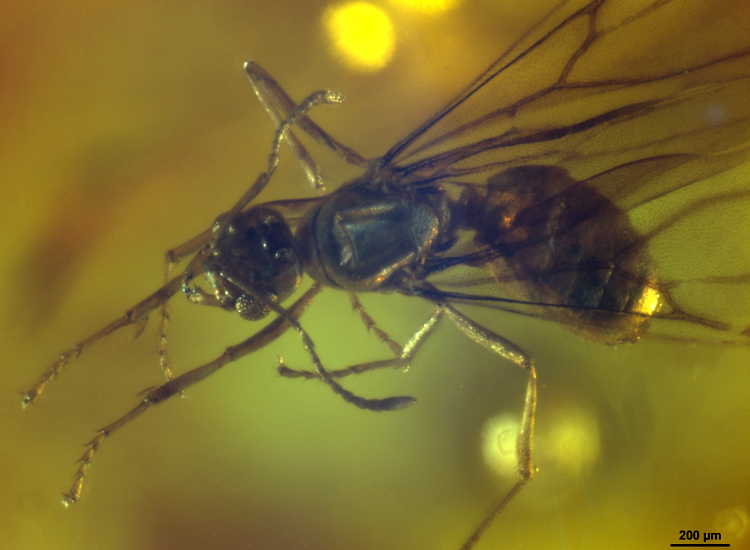

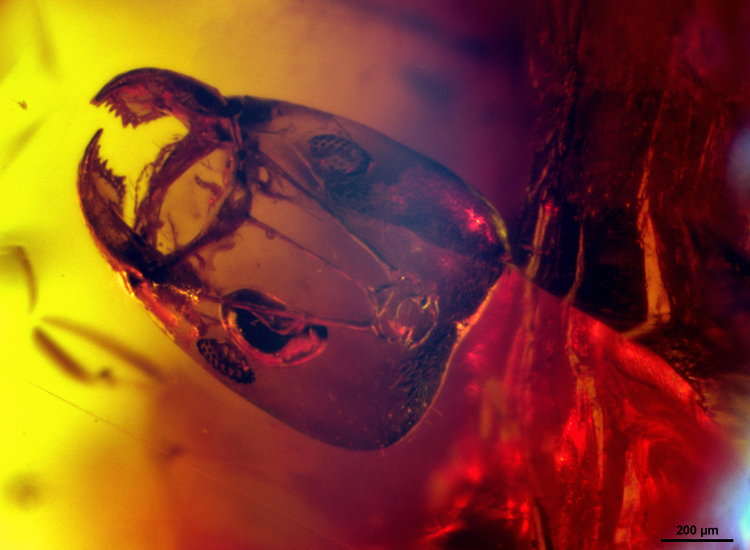

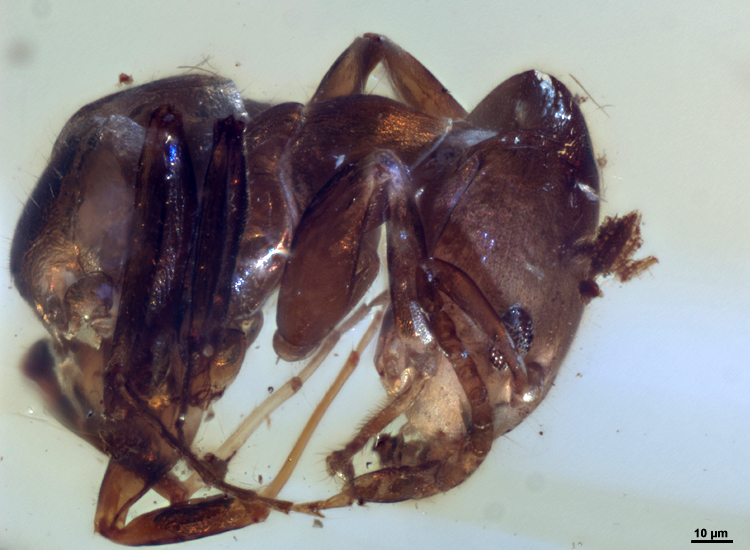

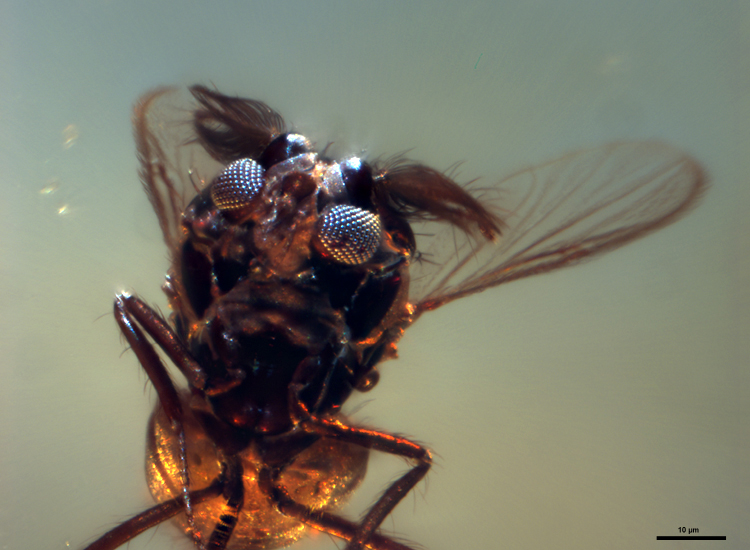

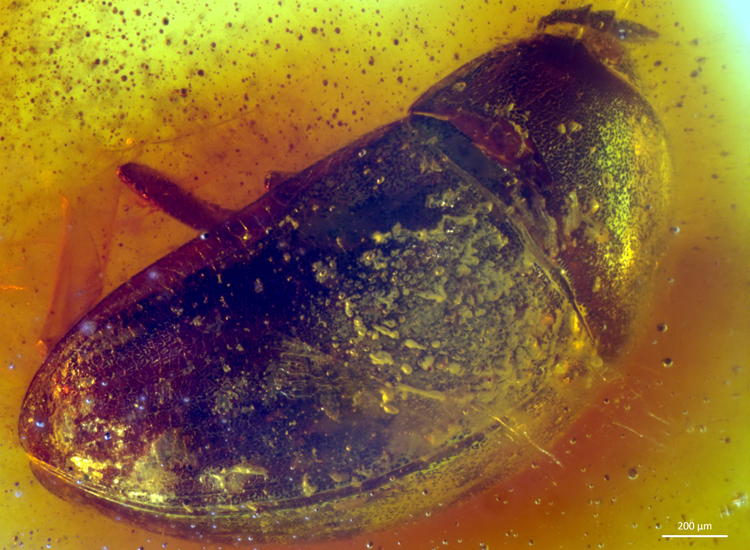

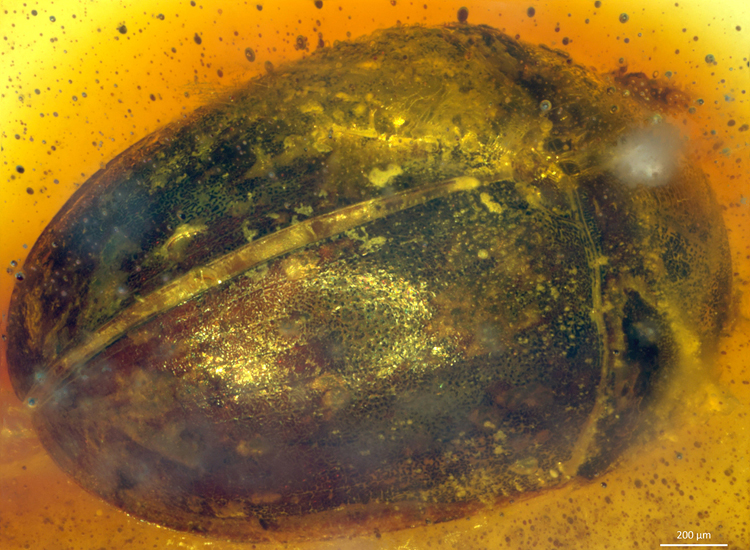

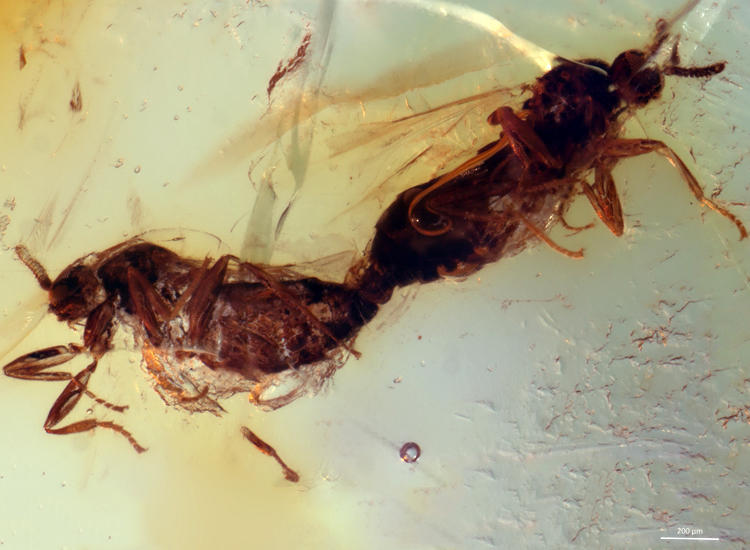

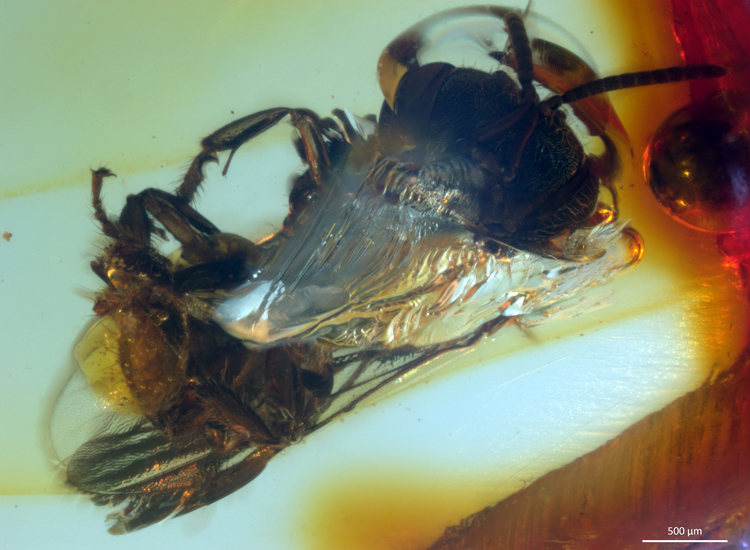

PRI Center for Paleontology researchers and volunteers have already found an astonishing array of insects and other arthropods in the Sanderson collection, including flies, wasps, and spiders. They have also found a handful of flowers and some mammal hairs.

Here are some of our recent findings in the Milton Sanderson Collection. The collection has many untold treasures hiding within, just waiting to be discovered. Stay tuned for more images in the upcoming months!